Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 1

School Nurse’s

Mental Health

Toolkit

Practical Strategies for Helping Students

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 2

School Nurse’s

Mental Health Toolkit

Practical Strategies for Helping Students

About This Guide ............................................................................................................................................ 3

Mental Health Action Signs for School Nurses ..................................................................................... 4

Coping and Relaxation Strategies ............................................................................................................. 5

Anxiety ................................................................................................................................................................ 7

Panic Attacks ..................................................................................................................................................... 8

School Avoidance ............................................................................................................................................ 9

Depression ....................................................................................................................................................... 10

Depression: Signs of Depression .......................................................................................................... 10

Depression: Strategies to Help...............................................................................................................11

Depression: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ...................................................................................... 12

Preventing Suicide ........................................................................................................................................ 13

Preventing Suicide: Signs of Ideation ................................................................................................. 14

Preventing Suicide: Strategies and Resources ................................................................................ 15

Self-harm .......................................................................................................................................................... 16

Self-harm: Self-harm vs. Suicidal Behavior........................................................................................ 16

Self-harm: Signs of Self-harm ............................................................................................................... 17

Self-harm: Strategies to Help ................................................................................................................ 18

Anger ................................................................................................................................................................. 19

Anger: Strategies to Help ........................................................................................................................ 19

Anger: The Anger Thermometer..........................................................................................................20

Resources ........................................................................................................................................................ 21

Copyright

©

VA-AAP - School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit

2024 Edition

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 3

About This Guide

America’s children spend nearly 1,000 hours a year in school.

Who do these kids go to when experiencing mental health distress?

A school nurse.

This toolkit was born from a collaboration in Virginia between school

nurses and pediatricians to learn and partner together to support

children and families with evidence-based tools.

The toolkit is owned by the Virginia Chapter of the American Academy

of Pediatrics. The Resource for Advancing Children’s Health Institute

was instrumental in content writing.

Special thanks to Lisa Hunter Romanelli, PhD.

Virginia schools can order a copy of the toolkit for

their health clinic or download a digital copy from

the VDH School Health webpage:

VDH.Virginia.gov/school-age-health-and-

forms/school-health-guidelines-and-

resources/.

Acknowledgments and Gratitude

Virginia Chapter, American Academy of Pediatrics

School and Mental Health Committees

Jacqueline Cotton, MD, FAAP, project lead, Mental Health

Committee Co-Chair

Leah Rowland, MD, FAAP, project lead, School Health

Committee Co-Chair

Percita Ellis, MD, FAAP, VA-AAP Treasurer, Rural Health Champion

John Farrell, MD, FAAP, School Health Committee Co-Chair

Paula Fergusson, MD, FAAP

R. Emily Gonzalez, PhD, Immigration Health Co-Chair

Amy Harden, MD, FAAP

Paige Perriello, MD, FAAP, Central Virginia VA-AAP Delegate

Kristina Powell, MD, FAAP, VA-AAP President

Bethany Geldmaker, PhD, PNP, VA-AAP grant administrator

Tammy Shackelford, administrative lead,

Virginia Mental Health Access Program

School nurse leadership contributors:

Joanna Pitts, BSN, RN, NCSN, CNOR (lead)

Angela Knupp, BSN, RN

Tammy Miller, BSN, RN, QMHP

Heather “Shea” Pugh, BSN, RN

Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters,

graphic design and publication support.

This resource is supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling

$1,167,341 with 20% financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by

HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

This resource is being made available by the VA-AAP to the general public and is for informational purposes only. The views expressed in this resource should not necessarily be

construed to be the views or policy of the VA-AAP, or any partners in this work.

The information in this resource is believed to be accurate. However, the VA-AAP does not make any warranty regarding the accuracy or completeness of any information provided. The

information is provided as-is and VA-AAP and its partners expressly disclaim any liability resulting from use of this information. The information in this resource is not, and should not

be relied on as medical, legal, or other professional advice, and readers are encouraged to consult a professional advisor for any such advice.

In addition, this resource is not a substitute for the exercise of one’s independent professional judgment, which shall be exercised in the sole discretion of the individual. No part of this

resource may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the VA-AAP.

Download a digital copy and learn more about

the Virginia Chapter of the American Academy

of Pediatrics:

VirginiaPediatrics.org/school-

nurse-toolkit/

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 4

Mental Health Action Signs for School Nurses

Mental Health Action Signs for School Nurses

Despite well-documented levels of emotional and behavioral problems in the nation’s youth, studies

have repeatedly shown that 75% of youth with these problems are not identified and do not receive

needed care.

The REACH Institute offers the “Actions Signs” Project toolkit to help caregivers, educators, and healthcare

professionals identify children at behavioral and emotional risk. If you think that one of your students may

have any of the following signs, take immediate action, collaborate with your school’s mental health team,

and follow your school’s protocol to help your student feel better.

• Feeling very sad or acting withdrawn for more than two weeks.

• Seriously trying to harm or kill themselves, or making plans to do so.

• Sudden overwhelming fear for no reason, sometimes with a racing heart or

fast breathing.

• Involved in many fights, using a weapon, or wanting to badly hurt others.

• Severe out-of-control behavior that can hurt them or others.

• Not eating, throwing up, or using laxatives to make themselves lose weight.

• Intense worries or fears that get in the way of their daily activities.

• Extreme difficulty in concentrating or sitting still that puts them in physical

danger or causes school failure.

• Repeated use of drugs or alcohol.

• Severe mood swings that cause problems in relationships.

• Drastic changes in behavior or personality.

To download the “Actions Signs” Toolkit, scan the code or visit

Flipsnack.com/reachcatie/actionsigns.html.

For more information about youth mental health support,

r

esources, and tools, visit TheReachInstitute.org.

TheReachInstitute.org

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 5

Coping and Relaxation Strategies

Coping and Relaxation Strategies

It is difficult to learn something new when we are anxious, angry, or distracted.

Teach and practice coping skills when everyone is calm.

Breathing Techniques

Belly Breathing

• When we are anxious, we breathe from our chest.

• Belly breathing stimulates the vagus nerve which

activates the relaxation response.

• Exhale longer than inhale for increased effect.

Young Children:

• Lie down so the back is supported by a surface

(couch/floor).

• Place a toy on the belly and watch it rise and fall.

Learn to belly breathe with Elmo:

Visit YouTube.com/watch?v=_mZbzDOpylA

or scan the code.

Older Children:

• Blow on pinwheel for

prolonged exhalation.

• Imagine filling room with a color while exhaling.

Teens:

• Hand on sternum, hand over belly button and focus

on moving hand on abdomen only.

• Counting inhale/exhale pattern: 4 second inhale,

7 seconds exhale.

Belly breathing video demo for

older kids: Visit YouTube.com/

watch?v=OXjlR4mXxSk or scan

the code.

Box Breathing

• Exhale to a count of four.

• Hold with lungs empty for four counts.

• Inhale to a count of four.

• Hold the air in your lungs for a count of four.

• Exhale to a count of 4 and start over.

Learn to box breathe:

Visit YouTube.com/

watch?v=G25IR0c-Hj8 or

scan the code.

Take 5 - Combines breathing and sensory input.

• Trace one hand with the finger on the opposite hand.

• Breathe in deeply as you trace your thumb from base

to tip.

• Breathe out as you trace back to your palm.

• Breathe in as you trace to the tip of your index finger.

• Breathe out as you trace back to your palm.

• Go around your whole hand.

• Can do this under the desk at school.

54321 Coping Strategy

54321 (or 5, 4, 3, 2, 1) is a grounding technique to reduce anxiety or stress. Tell the

student: Identify 5 things you can see, 4 things you can touch, 3 things you can hear, 2 things

you can smell, and 1 thing you can taste.

For video demo, visit Strong4Life.com/en/emotional-wellness/coping/grounding-your-

body-and-mind or scan the code.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 6

Coping and Relaxation Strategies

Coping and Relaxation Strategies

Muscle Relaxation Technique

Progressive Muscle Relaxation or “Body Scan”

When we are anxious our bodies respond with muscle tension. Progressive muscle relaxation reduces muscle tension

and associated anxiety.

• Tense muscles first – from head to toe – and then release. This allows easier letting go of muscle tension all over the

body.

• This can be done without others noticing, even while in class.

• Squeeze fists as tight as you can (under desk or in pockets) for 10 seconds, then release.

• Squeeze knees together as tight as you can (under desk) for 10 seconds, then release.

For video demo, visit Strong4Life.com/en/emotional-wellness/coping/practicing-progressive-

muscle-relaxation or scan the code.

For video demo for older children, visit YouTube.com/watch?v=8Xp2UzG7UYY or scan the code.

Distraction Strategies

• Choose an item you can see in front of you. Spell it out, forward and then backward.

• Pick a color and name everything you can see that matches that color.

• Hum a song quietly.

• Think about your favorite TV show. Try to remember all the actors’ names and what they were last wearing.

• Focus on one object and think about how you would change each aspect of its design.

• Choose a category (what you see around you, animals, countries, people, food, etc.) and try to name one item for

each letter of the alphabet.

Ways to distract yourself at home:

• Listening to music.

• Watching TV.

• Reading.

• Drawing.

Door Method Relaxation Technique*

This technique can be helpful for falling asleep, staying calm, and

reducing distractions.

• Picture four doors, all hiding a place or something that brings joy.

• Pick a door you want to go in and walk in. What do you see there?

Look around and describe all that you experience - sights, sounds,

and smells.

*Door Method by Tamar Chansky from “Freeing Your Child from Anxiety”, 2004.

The

Beach

Grandma’s

House

The

Park or

Playground

Kittens

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 7

Anxiety

Anxiety

Everyone experiences anxiety. Anxiety is a common emotion and can be helpful or harmful.

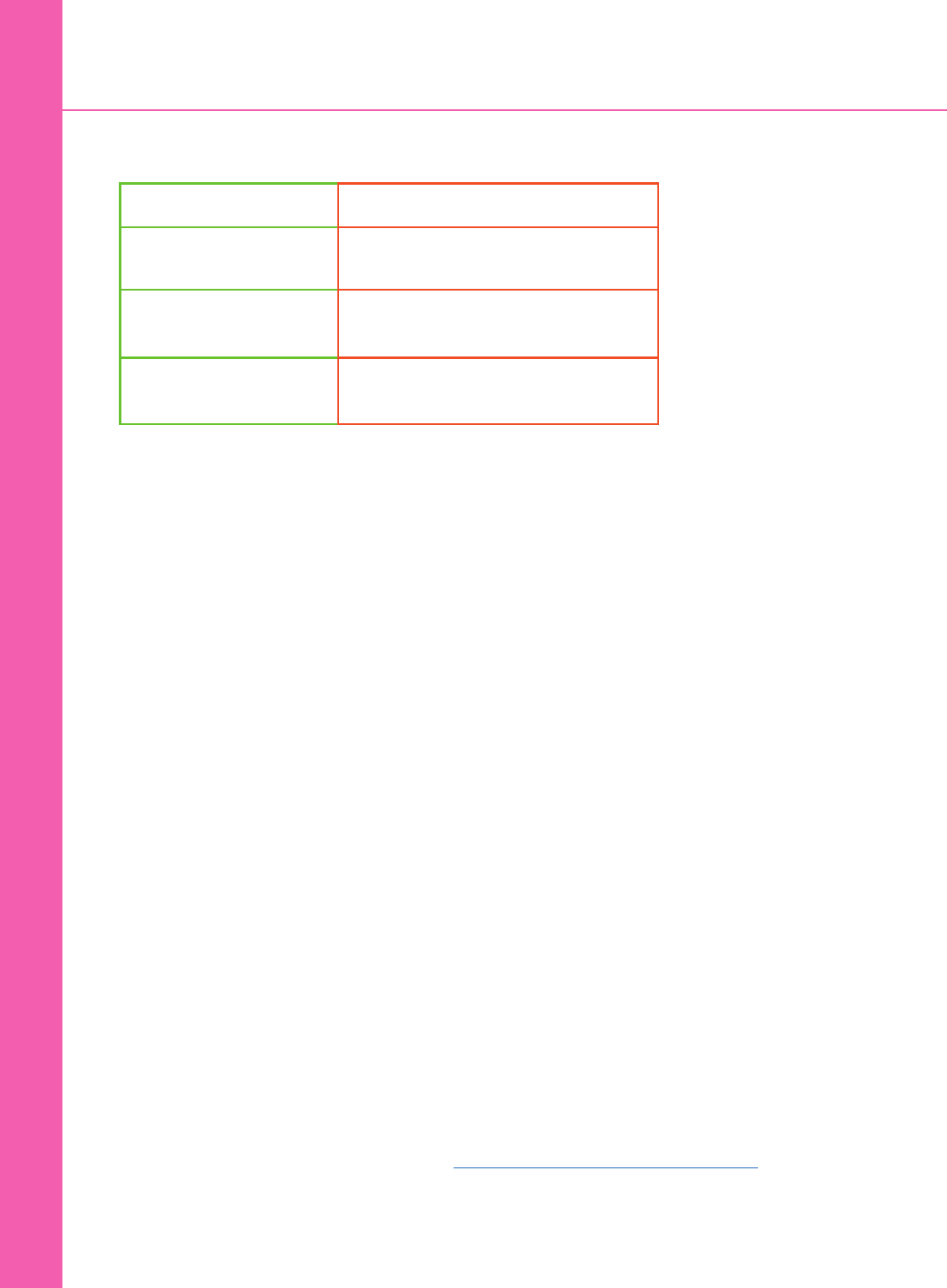

Anxiety is helpful: Anxiety is harmful:

To protect us when there is

a real threat.

When we see threats everywhere.

To alert us to a stressful

situation.

When we overestimate threat so that

most situations are stressful.

To help us face new

challenges.

When we avoid daily activities and new

challenges.

Past or present trauma can provoke

anxiety symptoms.

Students with severe anxiety can

have self harming behaviors or

suicidal thoughts.

Signs of Anxiety

Academic signs:

• Frequent trips to the nurse.

• Leaving school early or arriving late.

• Skipping school activities (e.g., gym, lunch,

or recess).

• Excessive absenteeism.

• Sleeping in class.

Student might report:

• Physical complaints (stomach aches, headaches,

chest pain, racing heart, trouble breathing, feeling

dizzy).

• Excessive worry or fears.

• Trouble concentrating.

• Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen.

• Trouble sleeping.

Signs others might see:

• Restlessness.

• Irritability or acting out.

• Using marijuana or other drugs to ease distress.

• Change in participation in normal activities.

• Not wanting to engage with friends or activities.

Immediate Strategies

Listen and support.

Let the student know that you hear how they are feeling

and that you are there to help.

Communication Tips

• Validate the student’s feelings: “It sounds like you’re

worried about ...That must be very hard.” Avoid saying

“Everything is fine,” “Don’t worry,” or “That’s not a big

deal.”

• Check your feelings. Be calm, so you can calm the

student.

• Gather information without judgment. Be curious.

• Do you know why you’re feeling worried?

• What challenges are you having at home or

school?

• How are your worries affecting your sleep and

concentration?

• How do your worries make it hard to do what

you normally do?

• How often does this happen?

• Explain anxiety. Let the student know that everyone

gets anxious. Anxiety is helpful when there is a real

danger or true alarm. Sometimes, we get a false alarm

and overestimate the threat.

Review the Cognitive Behavior Triangle - Visit the Depression section in this guide.

Students with severe anxiety can be treated with therapy or medication or both. Changing one piece of the triangle

(e.g., improving self-talk/thoughts) affects feelings and behavior. For example, changing a thought from “I’m going

to fail this test” to “I studied and I’ll do my best” can decrease anxiety (feeling) and improve concentration (behavior).

Changing behavior (deep breathing exercises) can improve anxiety (feeling) and help thoughts become more positive.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 8

Panic Attacks

Panic Attacks

A panic attack is a period of intense fear or discomfort during which at least four symptoms of anxiety

develop quickly and usually reach a peak within 10-20 minutes.

Students may experience panic attacks out of the blue or in response to a feared object or situation (e.g., a spider,

taking a test, giving a presentation).

Signs/Symptoms

During a panic attack, a student will experience at least four of the following symptoms intensely:

• Pounding heart or accelerated heart rate

• Sweating

• Trembling or shaking

• Shortness of breath

• Feelings of choking

• Chest pain

• Nausea or stomach pain

• Dizziness or lightheaded

• Numbness or tingling sensations

• Chills or hot flashes

• Fear of losing control or going crazy

• Fear of dying

• Feeling detached from reality

Strategies

Panic attacks are scary to experience and witness. You can help a student having a panic attack by:

Staying calm. Students are overwhelmed during a panic attack and may think they are going to die. By

staying calm and speaking to the student in a soothing voice, you can help them to relax more quickly.

Providing reassurance. Let the student know that they are experiencing a panic attack, it is scary, but

harmless and will pass. They are going to be fine. Reassure them that the symptoms will usually stop in

10 -20 minutes and you can help them feel better.

Showing the student how to slow down their breathing. A lot of the symptoms of panic are triggered

by over breathing (hyperventilating). Encourage the student to try to slow down their breathing by taking

slow, quiet, belly breaths in through their nose with their mouth closed and then out through their mouth.

The greater the panic, the more time it will take for a student to be able to slow down their breathing.

Helping the student feel more grounded. A variety of mental and physical grounding techniques can

help a student shift their focus away from the symptoms of panic. For example, try the 54321 technique

or apply cold water or an ice pack to the face and hands.

Gathering information. Once the student is calm, you can be curious and non-judgmental to find out if

this is happening frequently, and connect them with resources via your school protocols.

988

SUICIDE

& CRISIS

LIFELINE

Help them connect.

Always follow your school’s crisis protocols.

Call or text 24/7.

988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 9

School Avoidance

School Avoidance

School avoidance is the regular refusal to attend school or maintain consistent attendance. This can lead

to chronic absenteeism, missing 18 days or more of school within an academic year. The sooner school avoidance is

recognized, the better: not attending school is an emergency. Multiple factors contribute to school avoidance.

External factors:

• Bullying from a student or adult in

the building.

• Family violence, trauma, or

disruption.

• Family illness leading to separation

anxiety.

• Poverty, lack of access to resources,

need to work to support the family.

• Racism or LGBTQ+ discrimination.

• Natural disasters, violence in the

community.

Student factors:

• Mental health conditions

(depression, anxiety).

• Personal medical challenges

(e.g., constipation causing

student to avoid using the

bathroom at school).

• Chronic or acute medical

illness (e.g., diabetes,

concussion).

What others might see:

• Refusal to participate in class

activities (recess, PE, etc).

• Temper tantrums or outbursts,

crying, especially upon arrival to

school.

• Improvement on weekends or

breaks.

• Chronic tardiness or early

departures.

• Missing class, presentations,

or tests.

• Frequent clinic visits.

Strategies

Unmet needs contribute to school avoidance.

Develop a communication process and team within the school so nurses are made aware of students who are

missing school but may not be coming to clinic.

Check in with the student:

Ask open ended questions, starting with easy ones.

• Be curious and supportive – “You have been missed

lately! How are you?”

• Have you been sick? How have you been feeling?

• What do you like (or dislike) about school these days?

• Can you tell me about your friends? Are you being

bullied by anyone?

• Has anything scary happened at school?

• How is everything going at home? What kind of

changes are happening?

• Is there anything specific (classes or stressful

situations) that keeps you from school?

• If chronically tardy, say: “I see you are often late in

the morning. What do your mornings look like? How

is everything at home? How can I help?”

Provide personalized early outreach to families.

The longer a child misses school, the harder it is to

return. Connect with an open mind:

• “I am calling to see how we can support you and

[student] in order for [him/her] to be in school

regularly. Are there any specific reasons that your

child has been absent?”

• If chronically tardy, ask: “Are there ways we can

help your child arrive on time?”

• Recognize that stepwise approaches can be

helpful. Consider a 504 plan for gradual re-entry

to school.

• Connect families to local resources.

See Bridge2ResourcesVA.org.

• Encourage a visit to their medical provider.

Encourage intra-school connectedness. A counselor, trusted teacher or coach, extra curricular activities,

and clubs help students’ motivation to attend. Who can be on the support “team” for the student?

Recognize when students need a 504 plan or IEP for unmet medical or educational needs.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 10

Depression

Depression

Depression is a mood disorder that affects how we think, feel, and act.

It can be described as overwhelming sadness that persists, interfering with everyday life.

For at least two weeks, students may

experience:

• Excessive sadness (may see irritability or

anger).

• Loss of interest in activities.

• Change in appetite, may see weight loss

or gain.

• Sleeping too much or too little.

• Feeling restless or hard to get moving.

• Fatigue and trouble concentrating.

• Feelings of guilt or low self-esteem.

• Thoughts of death or dying.

Did you know?

• Risk factors for depression include a family history of depression, stress, co-existing mental health disorders, and

chronic medical illnesses.

• Younger students present more often with physical complaints such as chronic abdominal pain and recurrent

headache.

• Black youth are less likely to seek help and less likely to remain in counseling.

• LGBTQ+ youth are SIX times more likely to be depressed.

ASK

Depression can be associated

with suicidal thoughts, plans, or

attempts. One caring adult can

save a life! There is NO EVIDENCE

that asking about suicide increases

its risk. Don’t wait to take action!

Quick Strategies

• Approach with curiosity,

not judgment.

•

A

sk open-ended

questions.

•

O

ffer hope.

Signs

Thoughts:

• Circular negative thinking: “I’m not good

enough, nothing is going to get better.”

• Emptiness or numbness. A lack of joy.

• Suicidal thoughts: “It’s not worth it to go on.”

Actions:

• Dropping out of activities.

• Not spending time with family or friends.

• Staying in their room at home.

• Self-harm.

Behaviors noticeable to others:

• Distancing, withdrawal, acting out.

• Change in friend groups or isolation.

• Concerning social media activity.

• Decline in hygiene or no longer caring about appearance.

• Changes in eating habits (e.g., not eating lunch).

Academic changes:

• Skipping classes.

• Acting out in class toward teachers or peers.

• Falling asleep in class.

• Decline in academic performance.

• Difficulties concentrating.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 11

Depression

Depression

Strategies

School nurses can do a lot to help

depressed students.

Approach with curiosity, not judgment.

Ask open-ended questions.

“I have seen changes that make me wonder about you.

Are you doing OK? How are you feeling?”

“I see you are really struggling. Is there anything you

would like to talk about?”

“I have heard others say I just want the pain to go away –

how about you?”

Offer hope. Share information about depression.

If you suspect a student may be depressed, you can

tell the student:

Depression is common but not normal.

Depression changes how we think, feel, and act.

Depression can cause physical changes.

Depression is treatable. Therapy, learning new skills,

and sometimes medication can help depression.

Encourage the student to share how they are

feeling with people they trust.

Depressed students need support, but may not let

people know how they are feeling. Encourage students

to let trusted friends, caregivers, teachers, and medical

providers know how they are feeling.

Notify appropriate school staff if you’re concerned

about the severity of the student’s depression or

suspect the student is suicidal.

Know your school’s protocol and crisis team before a

crisis, and follow up after referral.

Communicate with caregivers and providers.

Encourage families to contact medical providers

about your concerns so they can collaborate to make a

treatment plan.

Visit Bridge2ResourcesVA.org or scan

the code to help families identify local

mental health resources.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy shows the connection between feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. If we can recognize

these interactions, we can figure out ways to feel better when we are experiencing distress.

• Teach calming methods to relax the mind and body. See Coping and Relaxation Techniques section in this guide for

more information.

• Change your behavior or environment. Go outside, find a friend, listen to music, draw, or move the body (shoot

baskets, kick a soccer ball, or walk).

• Create a toolbox. Help them write down strategies that work. What can the student do the next time they feel sad?

• Explore ways to create healthy routines. Getting adequate sleep and nutrition, reducing screen time or social media

use, exercise, or increasing free time and friend time matters to well-being.

• Follow school protocols for mental health referrals when depression is moderate or severe, and/or has been occurring

for longer than two weeks.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 12

Depression

Depression

Helpful cognitive behavioral strategies for depression are gifts that a nurse can give students in the moment.

They include:

Thoughts – Depression is associated with negative thoughts and core beliefs such as, I am unlovable, I am

worthless, and I am helpless. Changing thoughts can help change feelings and behaviors (see CBT triangle). Some

questions that can help students “put their negative thoughts on trial” are:

• “Is this thought helping or hurting me?”

• “What is the evidence for and against the thought?”

• “Is there a more helpful and realistic thought?”

• “What would my friends say?”

Feelings – Encourage students to cope with feelings of immediate sadness by doing something that is fun and

distracting, soothing and relaxing, or that expends energy.

• Increase pleasurable activities.

• Teach the student: depression may tell you to stay home by yourself, but put yourself into positive situations

even if you don’t feel like it and see what happens.

• What does the student like to do? Help the student identify and schedule fun: exercise, art, music, writing,

group or family activities.

Behavior – Unpleasant situations, interpersonal conflicts, and stressors can contribute to depression. If these things

are under the student’s control, encourage problem solving. Key steps for problem solving are:

1. Problem Identification (what is the problem?)

2. Identify Choices (what choices can I make?)

3. Consequences (what might happen if I make that choice?)

4. Choose a Solution (make a decision and go!)

Thoughts

FeelingsBehavior

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 13

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

988

SUICIDE

& CRISIS

LIFELINE

One caring person can save a life…

You are that person.

Prevention of suicide involves

identifying students who have:

• Thoughts of death or hurting

themselves.

• A history of prior attempts.

• A specific plan.

• A family history of suicide.

Risk factors include:

• Bullying.

• Chronic illness.

• Depression or other mental health

disorders.

• Inability to obtain care for mental

health.

• Societal pressures (racism, poverty, or

trauma).

• Stigma and cultural barriers.

• Substance abuse.

• Access to lethal means.

Firearms are

used in more

than 50% of

suicides.

Help them connect.

Always follow your school’s crisis protocols.

Call or text 24/7.

988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

To text 988 in Spanish, type “Ayuda” to connect with a Spanish-speaking counselor. For people who speak

other languages, call 988 for translation in 240+ languages. This is available 24/7 through voice calling only.

ASK

There is NO EVIDENCE

that asking about

suicide increases its risk.

Quick Strategies

• Approach with

curiosity, not

judgment.

• Ask open-ended

questions.

• Offer hope.

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 14

Suicide rates are higher for:

• Black youth - Rates of suicide for Black youth have risen faster than in any other racial/ethnic group in the past

two decades.

• LGBTQ+ youth.

• Native Americans and Alaska natives.

• Those with disabilities (due to difficulties in communicating suicidal thoughts).

• Residents of rural areas.

Signs

Noticeable Behaviors

• Withdrawal or reports of severe pain.

• Extreme mood swings, including irritability or anger.

• Giving away prized possessions.

Actions

• Talking about wanting to die.

• Making or researching a plan to die.

• New or increased substance use.

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

Suicidal Ideation in Students

In 2021, approximately 3% of

all students reported making

a suicide attempt that

required treatment.

In 2021, suicide was the second

leading cause of death for youth

ages 10-14 and ages 20-34.

In 2017, nearly 1 in 5 students

had thoughts of suicide. This

increased to 1 in 4 during

the pandemic.

Thoughts

• Frequent thoughts about death or dying.

• “I don’t want to live.”

• “Everyone would be better off without me.”

• “It’s all my fault.”

Academic Signs

• Withdrawal from activities or declining grades.

• Chronic absences.

• Dramatic change from prior performance.

For additional resources for mental health conditions associated with suicidal ideation for

additional resources for mental health conditions associated with suicidal ideation, scan

the code or visit TheREACHinstitute.org/help-for-families/helpful-resources/. For additional

resources about suicide prevention, visit the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

at AFSP.org.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 15

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

Preventing Suicide: How to Help

988

SUICIDE

& CRISIS

LIFELINE

Strategies

Approach with curiosity, not judgment.

“This is a horrible way to feel, but there is help and hope for feeling better.”

“Thank you for sharing these thoughts. I am here with you.”

Ask open-ended questions.

“Sometimes kids feel so low that they wish they were never born. How about you?”

“Sometimes when people feel this bad, they wish they were dead or not here anymore.

Tell me about you…”

“Have you ever done something to hurt yourself or tried to kill yourself?”

Offer hope.

“These feelings are treatable. Therapy, learning new skills, and sometimes medication can help.”

“You are not alone. Many kids have experienced the same feelings and have gotten better.”

Additional Resources

Download the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions toolkit at NIH.NIMH.gov. These screening questions can be

completed with a student in one minute to determine if they need emergent care.

Visit SuicideSafetyPlan.com for the The Stanley Brown Safety Plan (also available for

download in the Apple App Store or scan the code).

Safety planning is an essential part of treatment. For more information, visit AFSP.org.

Having a safety plan that addresses the following is an essential component of a student’s recovery:

• Recognize what puts a student at risk.

• Find coping strategies that do not rely on the presence of others.

• Engage with people and go to places that help distract students away from their problems.

• Reach out to family or friends that can help students in a crisis.

• Keep the student’s environment safe.

• Consider sharing the home safety checklist with families: AACAP.org/AACAP/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/

Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/suicide-safety-130.aspx.

Keep the student safe with you while you contact school resources.

Connect and communicate with school staff, caregivers, and pediatric clinicians. Know your school’s protocol and

crisis team before a crisis, and follow up after referral.

Help them connect.

Always follow your school’s crisis protocols.

Call or text 24/7.

988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

To text 988 in Spanish, type “Ayuda” to connect with a Spanish-speaking counselor. For people who speak other

languages, call 988 for translation in 240+ languages. This is available 24/7 through voice calling only.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 16

Self-harm

Self-harm

Self-harm (non-suicidal self-injury) occurs when a person

hurts oneself on purpose.

ASK

Suicidal thoughts can

be present in a person

who self-harms (but

self-harm does not

automatically mean a

person wants to die).

• Behavior might be a momentary escape

from intense distress such as loneliness,

sadness, fear, or shame.

• Sometimes it is hard to stop because it

helps them feel better.

• Self-harm can be a way to take control

when everything else is out of control

(family conflict, bullying, or trauma).

Did you know?

• Self-harm is a cry for help.

• Kids and teens with mental health

conditions are at the highest risk for

self-harm. These include:

• Depression.

• Substance abuse.

• Sexual abuse.

• Severe abuse or abuse by a

family member.

• Anxiety disorders.

• Eating disorders.

• PTSD.

• Borderline personality disorder.

• Average onset for self-harm is 15 years

old but females are more likely to be

younger.

• Of people who self-harm, 25% only

have one episode.

• The majority of people who self-harm

stop after a period of five years.

• Severity of self-harm can range

from superficial wounds to lasting

disfigurement.

Self-harm might include:

• Cutting.

• Burning.

• Hair pulling.

• Skin-picking or biting.

• Hitting or punching self with intent to

cause harm.

• Risky behaviors (trying to get hurt on

purpose).

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 17

Self-harm

Self-harm

WHY?

What are some

possible reasons

a person would

s

elf-harm?

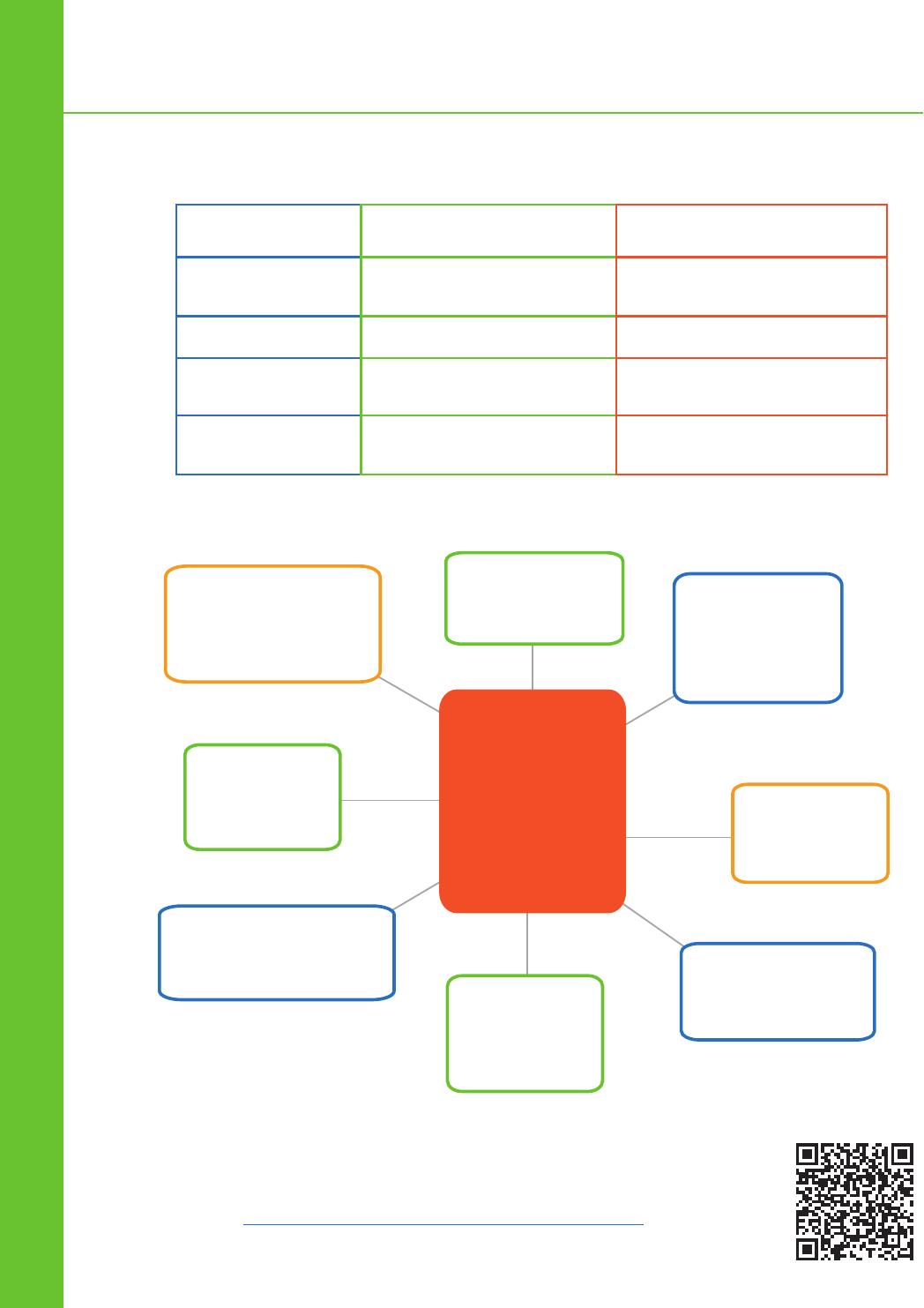

Self-harm vs. Suicidal Behavior

Self-harm Suicidal Behavior

Intent

To get immediate relief from

negative emotions

To die in order to permanently

escape pain

Repetition

More frequent Less frequent

Lethality

Less lethal means but potential

for fatality

Tends to involve more lethal

means

Psychological

Consequences

Often used to relieve

psychological pain

Often aggravates psychological

pain

To have an

energy rush and

feel good.

To feel in

control of body

or mind.

To relieve

stress or

pressure.

To feel

something.

Sometimes there is

no distinct reason.

To cope

with a history

of trauma.

To cope with anxiety

or negative feelings.

To distract

o

r purify

th

emselves.

WHY? self-harm graphic data is provided by the Cornell Research Program on Self-injury

and Prevention. For more information on self-injury, intervention, and treatment, scan

the code or visit SelfInjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/siinfo-2.pdf.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 18

Self-harm

Self-harm

Signs

What you might see:

• Scars often in patterns (hands, arms, thighs, stomach).

• Fresh cuts or wounds.

• Wearing long sleeves or long pants to hide injury even in hot weather.

What you might hear from the student:

• Frequent reports of accidental injury or risky behavior.

• Problems in relationships with family or peers.

• Mood changes that are impulsive or intense.

• Signs of depression or anxiety.

• Abuse of alcohol, marijuana, or drugs.

• Asking for bandages but not showing wounds.

What peers or family might see:

• Spending time on websites, message boards, or social media devoted to self-harm.

• Exchanging texts devoted to self-injury topics.

• Exchanging photos of self-harm wounds.

• Talking about self-harming behaviors in general or about self-harming thoughts.

Strategies

Approach with curiosity, not judgment.

Ask open-ended questions.

“Sometimes, when some kids are stressed, they hurt themselves on purpose.

Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose without intending to die?”

“I’ve seen those scars on your arms and I think you might be hurting yourself.

If you are, I want you to know that you can talk to me about it.”

Asking questions does not make the student engage in self-injuring behavior.

Offer hope.

“You are not alone. Many students have experienced the same feelings and have gotten better.”

“These feelings are treatable, and you can develop safer ways to deal with negative feelings than

hurting yourself.”

Keep the student safe with you while you contact school resources.

Connect and communicate with school staff, caregivers, and pediatric clinicians. Know your school’s protocol

and crisis team before a crisis, and follow up after referral.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 19

We all experience anger.

Anger is a secondary emotion.

What is underneath?

Anger occurs when we feel attacked,

threatened, afraid, disrespected, or

humiliated.

Outbursts can be a sign of anxiety, depression,

trauma, stress, or poor emotional regulation.

Underlying mental health conditions or

challenging life situations can lead to anger.

Students often need support to learn how to

manage their anger and minimize the risk of

aggressive behavior.

Strategies

SAFETY FIRST: If a student is displaying anger AND aggressive behavior that is risky to the student and

others, follow your school’s crisis intervention plan.

Manage your own emotions. Angry students may trigger feelings of anxiety and anger in you. Before you can help,

you must manage your own feelings and remain calm. Raising your voice will escalate the student’s emotion.

Be aware of your own body language and position. Take a non-threatening stance and project calm.

Minimize demands on the student. When a student is angry, set aside demands (“lower your voice, sit down, show me

your pass”) until the student calms. Placing demands on an angry student is likely to increase their anger.

Offer supportive comments and choices. In the heat of an angry moment, students need to feel supported and to

calm down before they can engage in any problem solving:

• Say “I can see you’re really upset. Would you like to talk or take a few minutes to relax in my office?” This shows the

student that you understand and allows them to decide how you can help.

• Give choices to promote calm in the moment. Offer a quiet corner, reading, drawing, coloring materials, belly

breathing, 54321, music, or stress balls and other fidget items. Go for a walk with them.

• Listen without judgment. Students may need to vent without interruption, or talk through their feelings with you or

someone they trust. You don’t have to solve the problem in order to help.

Teach these ways to understand anger:

Mindfulness

Mindfulness helps us understand and deal

with distress and to purposefully observe one’s

own thoughts and feelings with kindness, not

judgment.

Encourage students to slow down, accept their

emotions, and focus on breathing.

Once the student is calm, explain that everyone

experiences anger. It can hurt us and others if we

don’t recognize it and know what to do.

Picture anger as a wave. Be mindful of when you’re at the top

of the wave, then ride the wave, waiting until anger levels fall.

The tension and “adrenaline” during peak anger is temporary

and students can learn to wait for it to pass. The wave

visualization can help the student manage their anger.

Picture anger like an iceberg. The anger shows, but there are

other emotions underneath. Ask: “Is your anger hiding another

feeling?” (e.g., sadness, worry, etc.)

Anger

Anger

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 20

Anger

Anger

The Anger Thermometer

Teaching students about how to measure their anger using an anger thermometer can help them manage anger.

Teaching The Anger Thermometer to Students

Show the student how the levels on the thermometer correspond to their emotions and bodily feelings.

How does the student feel and behave:

1. When they are most angry?

2. When they are in the middle or upset?

3. When they are peaceful?

4. When students learn about how anger feels in their body

and mind, relating to the anger thermometer, students can:

• Put words to their feelings.

• Start to employ different coping strategies.

• Identify when they need to calm down before acting.

10. I explode

9. Out of control

8. Furious

7. Very angry

6. Angry

5. Upset

4. Somewhat cranky

3. Restless

2. Still and calm

1. Totally at peace

Anger Management Quick Tips

Adapted with permission from Bunge et al. (2017).

Encourage students to practice using these strategies before their anger temperature rises to a high level.

Relaxation strategies – take a time out, belly breathing, applying cold over upper part of face with ice pack,

tensing and releasing muscles.

Mindfulness strategies – 54321, focusing on all your senses.

Distraction strategies – focusing attention on something else (e.g., favorite song, reading, coloring, exercising, object

in the room).

Changing thoughts – When we can identify unhelpful thoughts that fuel anger, and change them to helpful

thoughts, our anger can lessen. For example:

• They don’t control me. I’m not taking the bait.

• I can stay calm.

• As long as I keep my cool, I’m in control

.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 21

Resources

Resources

Always call 911 for any emergency or when safety is at risk.

Suicide

The Steve Fund Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741; and text STEVE to 741741 if a young person of color, for a trained crisis counselor, 24/7.

Suicide Hotline:

1 (800) 273-TALK (8255)

Self-harm

Young Minds UK - Self-Help Guide for Teens Who Self-Harm video

YoungMinds.org.uk/young-person/my-feelings/self-harm/#Whatisselfharm

Nip in the Bud - Learning about Children’s Mental Health through Film self-harm resources and videos

Nipinthebud.org/films-parents-category/self-harm/

The Cornell Research Program on Self-injury and Recovery -

The Non-Suicidal Self-injury Assessment Tool -

Selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/fnssi.pdf

Developing and Implementing School Protocol for Non-Suicidal Self-injury in School -

Selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/documents/schools.pdf

Educators and Self-injury: Manual for understanding and aiding students who self-injure.

EducatorsandSelfinjury.com/self%20injury-protocol/

Depression

MindDoc: Mental Health Support- App Download CBT Mood tracker, journal, symptom screener for anxiety and depression. Can also be used

with sleep disorders, eating disorders, postpartum depression, and various phobias. 10-question assessment directs user to learning modules.

Ages 12+, free with in-app purchases, available for download in the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Self Help Toons -

SelfHelpToons.com Free animated self-help video courses about therapy and mental health.

Boston’s Children’s Hospital Guided Self-Management Tools for Depression in Children Ages 6-12. Scan the code.

The ABCs of CBT: Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior Triangle Cognitive behavior therapy video.

YouTube.com/watch?v=Stw9P38ePVI

Anger

They Are The Future: Anger Thermometer Worksheet Pack - Free printable anger thermometer and parent guide

Theyarethefuture.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Free-Printable-Anger-Thermometer-Worksheets.pdf

Cookie Monster Practices Self Regulation by Life Kit Parenting and NPR - Video about practicing self control.

YouTube.com/watch?v=j0YDE8_jsHk

Mental Health Center for Kids: Videos on anger management for kids.

Anger Iceberg Activity - YouTube.com/watch?v=AQIQCOY_Im0

Strategies to Calm Down When Your Temper Rises - YouTube.com/watch?v=lxxpDF45TPA

Sesame Workshop Handling Angry Feelings for Kids Anger management video. SesameWorkshop.org/resources/handling-angry-feelings/

Panic/Anxiety

Rootd: Panic Attacks & Anxiety - App Download Panic Attack and Anxiety Relief tool. Free with in-app purchases.

Available for download in the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

K

ids Helpline Brain Basics: Panic attack informational video series for kids.

YouTube.com/watch?v=geoiskj4aUE

Mindshift CBT- Anxiety Relief App Download Anxiety and stress tools that include fear ladders, goal-setting tool; CBT to reduce worry, stress,

panic. From Anxiety Canada. Ages 12+, available for free download in the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Anxiety Canada -

AnxietyCanada.com

Free downloadable resources and tools for anxiety.

Fight Flight Freeze - A Guide to Anxiety for Kids video: Scan the code.

Fight Flight Freeze - A Guide to Anxiety for Teens video: Scan the code.

Boston Children’s Hospital -

Managing Anxiety in Childhood and Adolescence: Information and resource guide for parents and caregivers.

ChildrensHospital.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/bchnp-managing-anxiety-booklet.pdf

Child Mind Institute - ChildMind.org/topics/anxiety/ Resources for caregivers to support kids with anxiety.

988

SUICIDE

& CRISIS

LIFELINE

Help them connect.

Always follow your school’s crisis protocols.

Call or text 24/7.

988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

To text 988 in Spanish, type “Ayuda” to connect with a Spanish-speaking counselor. For people who speak other languages,

call 988 for translation in 240+ languages. This is available 24/7 through voice calling only.

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit | 22

Resources

Resources

LGBTQ+ Support

The Trevor Project

24/7, 365 crisis support for members of the LGBTQ+ community. Talk, text, or chat.

1 (866) 488-7386

TheTrevorProject.org

Trans Lifeline Peer Support US:

1 (877) 565-8860

The GLBT National Youth Talkline (youth serving youth – age 25):

1 (800) 246-7743

Trauma

Child Mind Institute Video and Guide: Helping Children Cope After a Traumatic Event: Scan the code.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network - Free resources on child trauma, trauma learning modules,

and tools to develop the systems to gain knowledge, to build practices, and to have the skills to support a trauma-sensitive school.

NCTSN.org/

School Avoidance

School Avoidance Alliance: School Avoidance 101 for Parents - Guide to helping kids get back in school.

SchoolAvoidance.org/school%20avoidance-101/

Rogers Behavioral Health School Avoidance and Refusal: What clinicians need to know. YouTube.com/watch?v=Rw-aBeSygm8

Space Treatment Overcoming Entrenched School Refusal: A six-point plan helping parents for getting school-refusing children back in school.

YouTube.com/watch?v=J4x4NW1S_po

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports:

Improving Attendance and Reducing Chronic Absenteeism - Scan code for clinician guide.

School Refusal Assessment and Intervention - Scan the code for clinician guide.

Coping and Relaxation

Mental Health Center for Kids: Grounding Exercises For Anxiety And Other Big Emotions video

YouTube.com/watch?v=5YtnpPPnqaY

Virtual Calming Room: Resource site for students, families, and staff to find tools and strategies for

managing emotions and feelings.

CalmingRoom.scusd.edu/home

The Virginia Tiered Systems of Supports

Led by the Virginia Department of Education to support divisions with implementing and

sustaining a multi-tiered system of supports. A systemic, data-driven approach that allows

divisions and schools to provide evidence-based practices and interventions to meet the

needs of their students. VTSSRIC.vcu.edu/

Other Mental Health Resources

Bridge 2 Resources

Access free or low-cost resources for housing, food, or healthcare in your community. Scan the code.

Bridge2ResourcesVA.org

National Center for School Mental Health (NCSMH): Mental health webinars from the University of Maryland School of Medicine

SchoolMentalHealth.org/webinars/

Stigma-Free Mental Health Student Mental Health Toolkit: Resources for teachers and counselors to help students ages 7-11 and 12-22

improve their mental wellness and combat stigma.

StigmaFreeMentalHealth.com/programs/school-program/student-mental-health-toolkit/

National Association of School Psychologists: The professional home for school psychologists. Site offers standard practice guidelines and a

variety of school-based mental health resources. NASPonline.org/

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration - Ready, Set, Go, Review: Screening for Behavioral Health Risk in Schools

SAMHSA.gov/sites/default/files/ready-set-go-review-mh-screening-schools.pdf

Mental Health @ Home: Free mental health workbooks to address a variety of mental illnesses.

MentalHealthatHome.org/2018/06/14/mental-health-workbooks/

Therapist Aid: Online Therapy Tools for Mental Health Professionals - Worksheets, interactive tools, videos, and articles.

TherapistAid.com/

Children’s Mental Health Matters: Maryland Public Awareness Campaign Resource Library

ChildrensMentalHealthMatters.org/resources/downloads/

RAINN Sexual Assault Hotline:

1 (800) 656-4673

National Helpline for Substance Use:

1 (844) 289-0879

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Helpline:

1 (800) 662-HELP or TTY 1 (800) 487-4889

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Pediatric mental health updates and resources.

A AC AP. or g

National Federation of Families: Family support and advocacy.

FFCMH.org

Children’s Defense Fund: Child advocacy and research.

ChildrensDefense.org

Mental Health America: Mental health screening tests.

MHANational.org

Draft

School Nurse’s Mental Health Toolkit

Practical Strategies for Helping Students

2024 Edition